Baiget, E.; Rodríguez, FA and Iglesias, X. ( 2016) Relationship Between Technical and Physiological Parameters in Competition Tennis Players . International Journal of Medicine and Sciences of Physical Activity and Sport vol. 16 (62 ) pp.243-255 Http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista62/artrelacion704.htm

Baiget, E.; Rodríguez, FA and Iglesias, X. ( 2016) Relationship Between Technical and Physiological Parameters in Competition Tennis Players . International Journal of Medicine and Sciences of Physical Activity and Sport vol. 16 (62 ) pp.243-255 Http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista62/artrelacion704.htm

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15366/rimcafd2016.62.005

ORIGINAL

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TECHNICAL AND PHYSIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS IN COMPETITIVE TENNIS PLAYERS

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TECHNICAL AND PHYSIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS IN COMPETITION TENNIS PLAYERS

Baiget, E. 1,2 ; Rodriguez, FA 3.5; and Iglesias, X. 4.5

1 Full Professor. Department of Physical Activity Sciences, University of Vic, Spain. E-mail: ernest.baiget@uvic.cat

2 Sport Performance Analysis Research Group (SPARG),University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia, Spain.

3 Full Professor. National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia, University of Barcelona, Spain. E-mail: farodriguez@gencat.cat

4 Full Professor. National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia, University of Barcelona, Spain. E-mail: xiglesias@gencat.net

5 INEFC-Barcelona Sports Sciences Research Group, National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia (INEFC), University of Barcelona, Spain.

UNESCO Code / UNESCO Code: 2411.06 Physiology of exercise / Exercise physiology.

Classification of the Council of Europe / Council of Europe Classification: 6 Physiology of exercise / Exercise physiology.

Received April 18, 2013 Received

April 18, 2013

Accepted July 9, 2013 Accepted July 9, 2013

ABSTRACT

In recent years, interest in evaluating physiological and technical parameters in tennis players has increased. Currently, there are tests that allow parallel recording of these parameters on the same tennis court. The objective of this study is to determine the relationships between technical and physiological parameters derived from the application of a specific resistance test in tennis. 38 competitive players performed a continuous and incremental test and technical parameters (technical effectiveness (TE), point of decay of technical effectiveness (PDET)) and physiological parameters (maximum oxygen consumption (VO 2max ), first and second ventilatory thresholds were recorded. (UV1 and UV2 ) ). A significant relationship was found between PDET and UV2 (r=0.65; p<0.05) and between ET and VO 2max (r=0.459; p<0.01). In conclusion, players with a better aerobic profile tended to obtain better ET results and a tendency to decrease ET was observed after the appearance of UV 2 .

KEY WORDS: tennis, specific resistance , technical effectiveness, maximum oxygen consumption, ventilatory thresholds.

ABSTRACT

In recent years there has been an increased interest to assess physiological and technical parameters in tennis players; currently there are tests that allow registering these parameters in parallel on the tennis court. The aim of this study is to determine the relationships between technical and physiological parameters resulting from the application of a specific endurance test procedure for tennis players. 38 competitive male tennis players performed a continuous and incremental field test and technical (technical effectiveness [TE], point of decreasing TE [PDTE]) and physiological parameters (maximal oxygen uptake (VO 2max ), first and second ventilatory thresholds (VT 1 and VT 2 )) were recorded. We found a significant relationship between PDTE and VT2 (r = 0.365, P < 0.05) and between TE and VO 2max (r = 0.459, P < 0.01). In conclusion, players with a better aerobic profile tended to get better results in terms of TE and showed a tendency to decrease TE from the appearance of VT 2 .

KEY WORDS: tennis,

specific endurance, technical effectiveness, maximum oxygen uptake, ventilatory thresholds.

INTRODUCTION

During a tennis match, a great diversity and volume of technical actions are executed. In Grand Slam tournaments, between 806 and 1,445 strokes per match have been recorded (Weber, 2003), and between 300 and 500 high-intensity efforts are made in a three-set match (Fernández, Méndez-Villanueva, & Pluim,

2006). Technical actions, in many cases, are carried out using high execution speeds. In service, players are capable of printing racket speeds between 100 and 116 km h -1 which corresponds to ball speeds between 134 and 201 km h -1(Kovacs, 2007). As an example, in 2012, the player Samuel Groth in South Korea performed the fastest service recorded in an official ATP (Association of Professional Tennis Players) competition, at a speed of 263 km h -1 . Most of these technical actions are performed in an open game environment and with a high precision component. Although it is very difficult to objectively assess technical performance in open game situations, hitting technical effectiveness (TE) in closed situations has been identified as a good predictor of competitive performance in tennis players (Birrer, Levine, Gallippi and Tischler, 1986; Vergauwen, Spaepen, Lefevre, and Hespel, 1998; Smekal,Pokan, von Duvillard, Baron, Tschan, & Bachl , 2000; Vergauwen, Madou, and Behets, 2004; Baiget, Fernández, Iglesias, Vallejo and Rodríguez, 2014).

The tennis player's ability to hit the ball, run and recover for the next point is largely determined by the physiological capacity to acquire, convert and use energy (Renström, 2002). The average physiological intensity recorded in simulated competition matches is around 50% of the maximum oxygen consumption (VO 2max ) ( Fernández, Fernández, Méndez and Terrados, 2005; Ferrauti, Bergeron, Pluim and Weber, 2001; Murias,

Lanatta, Arcuri and Laino , 2007; Smekal et al., 2003) and the mean concentrations of lactate in the game are less than 2.5 mmol·L -1 (Bergeron, Maresh, Kraemer, Abraham, Conroy and Gabaree,1991; Ferrauti et al., 2001; Murias et al., 2007; Smekal et al., 2003), there being moments in the game when its intensity raises these values up to 8 mmol·L -1 (Fernández et al., 2006).

During the game, points from a single hit alternate, as in the case of a service winner, and points played from the back of the court through long and intense exchanges. The unpredictability in the duration of the points, the choice of shots, the strategy, the total game time, the opponent or the climatic conditions influence the physiological request of tennis (Kovacs, 2006).

In recent years, there has been a considerable increase in interest in evaluating physiological and technical parameters through specific protocols carried out on the tennis court itself (Vergauwen, Spaepen, Lefevre and Hespel , 1998; Smekal et al., 2000; Vergauwen et al., 2004; Landlinger, Stöggl, Lindinger, Wagner, & Müller , 2012; Baiget et al., 2014). Hitting performance tests have been proposed in which the ability of players to direct the ball towards a certain area of the court is evaluated (Vergauwen et al., 1998; Vergauwen et al., 2004; Moya, Bonete, and Santos -Pink, 2010) or hitting speed and accuracy (Landlinger et al., 2012). For the evaluation of specific resistance, most tests use incremental tests (Smekal et al., 2000; Baiget, Iglesias and Rodríguez , 2008; Girard, Chevalier, Leveque, Micallef and Millet , 2006; Ferrauti, Kinner and Fernandez,2011; Baiget et al., 2014). There are protocols that evaluate load and physiological parameters by hitting simulation (Girard et al., 2006) or by hitting a fixed ball on a pendulum (Ferrauti et al., 2011). Specific resistance tests have also been proposed that allow physiological and technical parameters to be evaluated in parallel by recording hitting accuracy (Smekal et al., 2000; Baiget et al., 2008; Baiget et al., 2014). Although different variables derived from these tests have been described, such as the physiological parameters of oxygen consumption (VO 2 ) (Smekal et al., 2000; Baiget et al., 2014), blood lactate concentration (Smekal et al., 2000) or ventilatory thresholds (UV) (Baiget et al., 2014), and technical parameters such as percentage of hits (ET) (Smekal et al., 2000; Baiget et al., 2008; Baiget, Iglesias, Vallejo and Rodríguez , 2011; Baiget et al., 2014) or the point of decrease in technical effectiveness (PDET) (Baiget et al., 2008; Baiget et al., 2011), the relationships between these variables derived from their joint evaluation are not known.

OBJECTIVES

Given the relative importance of technical and physiological parameters in competitive tennis, and considering the possibility offered by the new protocols to evaluate these parameters at the same time, it seems appropriate to observe the relationships established between the different variables that can be evaluated by a specific test. Thus, the objective of this study is to determine the relationships between technical parameters and maximum and submaximal physiological parameters derived from the application of a specific resistance test in tennis in competitive players.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The present study has a descriptive correlational design and presents the results that were recorded in the same sample and circumstances as in the study published by Baiget et al. (2014).

Sample

A total of 38 competitive male tennis players (18.2 ± 1.3 years; height 180

± 0.0 8 cm; weight 72.7 ± 8.6 kg; mean ± SD) voluntarily participated in the study. Subjects were selected based on their level of competition. Their competitive level, assessed by the International Tennis Number (ITN), was between 1 (elite) and 4 (advanced)

(ITN 1= 8 players; ITN 2 = 10 players; ITN 3 = 9 players; ITN 4 = 11 players ).89.5% of the players had right lateral dominance. The subjects had a mean competitive training experience of 6.6 ± 2.0 years and maintained an average of 3.7 ± 0.5 and 1.5 ± 0.4 hours of technical-tactical and physical training per day, respectively. All subjects belonged to high-performance tennis training centers.

Process

Maximal and submaximal technical and physiological parameters were recorded using a specific endurance test performed on the tennis court (Baiget et al., 2014) modified from Smekal et al. (2000). It is a maximal, continuous, staggered protocol conducted by a ball launching machine ( Pop-Lob Airmatic 104, France ). ThePlayers had to perform alternate forehand and backhand shots at the rhythm imposed by the ball-throwing machine. Figure 1 is an illustrative diagram of the layout of the track and the spatial dynamics of the protocol used. Players were instructed to adjust their travel speed so that they arrived at the striking zone coinciding with the bounce of the ball. To ensure a homogeneous energy cost of the shots in relation to the technique used, only topspin forehand and backhand shots were allowed. The test began with a ball throwing frequency (FL P ) of 9 shots min -1

and the load was increased for periods of 2 minutes at a rate of 2 shots min -1

until the players were unable to follow the rhythm imposed by the machine, failing to hit two balls in a row. The ball throwing speed by the machine (68.6 ± 1.9 km h -1 , CV of 2.7%) and the wind speed (V wind < 2 m s -1) remained constant and were evaluated using a radar (Stalker ATS 4.02, USA) and a digital anemometer (Plastimo, France). The angle and height of the ball's exit through the launch tube of the machine with respect to the horizontal of the ground was 13° and 41 cm, respectively. The tests were administered between the months of February and April, in non-competitive periods and on a regulation outdoor tennis court, with a hard surface and medium speed (Green set®), previously marked with white tape. 40 new tennis balls (BabolatTeam®, Japan) homologated and approved by the International Tennis Federation (ITF) were used. The players did not participate in any high-stakes competition, test or training in the 24 hours prior to the test.P of 9 shots min -1 .

Figure 1 . Illustrative scheme of the test (Baiget et al., 2014).

physiological parameters

Gas exchange and pulmonary ventilation were continuously recorded using a portable gas analyzer (K4 b 2 , Cosmed, Italy). Data were recorded breath by breath and subsequently processed at mean values every 15 seconds. The recording began two minutes before the familiarization phase and ended five minutes after the end of the test. The general calibration of the measurement system was carried out at the beginning of each session (morning or afternoon), with an ambient air calibration before each test.

Se determinó como

parámetro fisiológico máximo el consumo máximo de oxígeno (VO2max) y

los valores submáximos se detectaron mediante los umbrales ventilatorios (UV)

calculados por los cambios en los parámetros ventilatorios identificando los

puntos de cambio de pendiente o de ruptura de la linealidad (Beaver, Wasserman y

Whipp, 1986).

Se determinaron los dos UV de acuerdo con el modelo propuesto por Skinner y

MacLellan (1980).

Primer umbral ventilatorio (UV1): Se determinó usando

los criterios de un aumento en el equivalente ventilatorio para el oxígeno (VE/VO2)

sin aumento en el equivalente ventilatorio de dióxido de carbono (VE/VCO2)

y el incremento no lineal de la ventilación pulmonar (VE).

Segundo umbral ventilatorio (UV2): Se determinó mediante

el incremento en el equivalente ventilatorio para el oxígeno (VE/VO2)

y en el equivalente ventilatorio de dióxido de carbono (VE/VCO2).

Consumo máximo de oxígeno (VO2max):

Se determinó mediante la observación de una meseta o estabilización en el VO2

o cuando el aumento en dos periodos sucesivos fue inferior a 150 ml·min-1.

Parámetros técnicos

De forma simultánea

al registro fisiológico se realizó una valoración objetiva de parámetros

técnicos registrados en tiempo real mediante el cálculo de las frecuencias

relativas (porcentajes) de aciertos-errores, evaluando tanto la precisión como

la potencia de los golpes mediante zonas marcadas en la pista (figura 1). Los

jugadores realizaron los golpes de izquierda a derecha de la pista

(derecha-revés) desplazándose en sentido lateral e intentando enviar la pelota

dentro de la zona marcada (diana). Los golpes se evaluaron como aciertos o

errores en función de los criterios de precisión (la pelota enviada por el

jugador debía botar en la diana) y de potencia (una vez la pelota había botado

dentro de la diana, debía sobrepasar la línea de potencia antes de realizar el

segundo bote). Para que un golpe se considerara como acierto debía cumplir los

dos requisitos (precisión y potencia).

Efectividad técnica (ET) (% aciertos): Cálculo objetivo del porcentaje de aciertos durante la prueba en

función de los criterios de precisión y potencia. Es el porcentaje de aciertos

por periodo y a intervalos de 30 segundos.

Punto de deflexión de efectividad técnica (PDET) (núm. periodo):

Punto de inflexión determinado mediante el último valor de ET por periodo a partir

del cual el sujeto está por debajo de su media de ET (media aritmética de los

valores durante toda la prueba) y ya no vuelve a superar este valor medio

(Baiget et al., 2008; Baiget et al., 2011).

Análisis

estadístico

La

normalidad de la distribución de las variables se evaluó mediante la prueba de

Kolmogorov-Smirnov. La relación entre las variables cuantitativas se estableció

con un análisis de correlación lineal, mediante el cálculo de coeficiente de

correlación lineal de Pearson (r). El nivel de significación se estableció en un valor de p

< 0,05. Todos los análisis se realizaron con el programa

estadístico SPSS para Windows 15.0 (SPSS Inc., EE.UU.).

RESULTADOS

La prueba tuvo una duración media máxima de 13:36 min:s correspondiente

a 6.6 ± 0.83 periodos. La tabla 1 muestra la relación entre los parámetros

técnicos representados por el PDET y la ET y los parámetros fisiológicos

representados por el UV1, UV2 y VO2max. Se observa una relación débil, pero estadísticamente

significativa, entre el PDET y el UV2. Este hecho sugiere que los

sujetos mostraron una tendencia a disminuir su ET a partir del UV2.

Por otro lado, la relación significativa moderada entre la ET y el VO2max,

indica que los jugadores con un mejor perfil aeróbico tienden a obtener una

mejor ET, y por lo tanto, a cometer un menor número de errores durante la

prueba.

Tabla I.

Coeficientes de correlación (r) entre los parámetros

técnicos (PDET y ET) y parámetros fisiológicos (UV1, UV2

y VO2max) registrados durante la prueba de resistencia específica.

|

Parámetros

técnicos |

|

Parámetros fisiológicos |

||||

|

|

UV1 (mL·Kg·min-1) |

|

UV2 (mL·Kg·min-1) |

|

VO2max (mL·Kg·min-1) |

|

|

PDET (periodo) |

|

0.306 |

|

0.365* |

|

0.332 |

|

ET (% aciertos) |

|

0.296 |

|

0.324 |

|

0.459** |

|

*Correlación significativa

p<0.05; **Correlación significativa p<0.01; PDET: punto de disminución

de efectividad técnica; ET: efectividad técnica; UV1: primer

umbral ventilatorio UV2: segundo umbral ventilatorio; VO2max:

consumo máximo de oxígeno. |

||||||

El PDET se detectó en el periodo 5.2 ± 1.1 correspondiente a un 80.6 ±

14.5% de periodo máximo conseguido. Este punto coincide con el periodo en que

se observa el UV2 en 10 sujetos, representando el 27.7 % de los

casos. Se encontró una relación estadísticamente significativa entre el PDET y

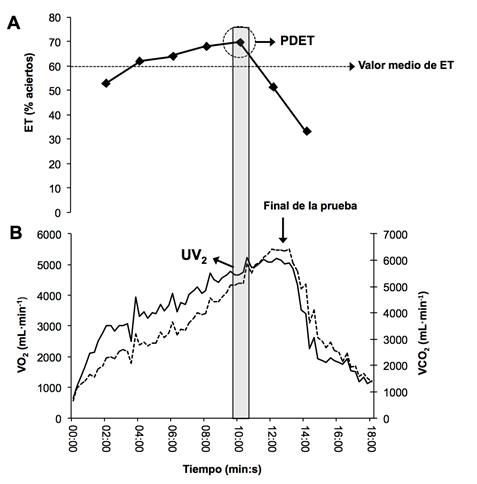

el periodo en que se observa el UV2 (r=0.408; p<0.05). La figura 2 muestra un ejemplo de la evolución de

los parámetros técnicos (ET) y fisiológicos (VO2 y VCO2)

a lo largo de la prueba en un sujeto. Se observa como en los primeros periodos

hay una ligera evolución positiva de la ET hasta que coinciden en el tiempo

(10:00 min:s; periodo 5) el parámetro técnico PDET y el parámetro fisiológico

submáximo UV2, a partir de este momento se produce un descenso

pronunciado de la ET.

Figura 2.

Evolución de la efectividad técnica (ET) (A), consumo de oxígeno (VO2)

y producción de dióxido de carbono (VCO2)

(B), a lo largo de la prueba en un sujeto. Se indica el punto de disminución

de efectividad técnica (PDET) (A) y el segundo umbral ventilatorio (UV2)

(B). Mediante la franja oscura se señala la coincidencia en el tiempo entre

PDET y el UV2.

DISCUSIÓN

Los resultados de este estudio indican que en el desarrollo de una prueba

de resistencia específica que evalúa paralelamente parámetros técnicos y

fisiológicos (Baiget et al., 2014), los jugadores con mejor perfil aeróbico

tienden a obtener mejores resultados de ET y que existe una tendencia a

disminuir la ET a partir de la aparición del UV2.

El tenis de competición es un deporte de elevadas exigencias tanto a

nivel técnico como a nivel fisiológico (Kovacs, 2007). Se han observado

relaciones entre el rendimiento competitivo en jugadores de competición y

parámetros tanto técnicos como fisiológicos (Birrer et al., 1986; Vergauwen et

al., 1998; Smekal et al., 2000; Vergauwen et al., 2004; Banzer, Thiel, Rosenhagen y

Vogt, 2008; Baiget et al., 2014). Aunque se ha descrito el perfil

fisiológico (Smekal et al., 2000; Baiget et al., 2008) y técnico (Vergauwen et

al., 1998; Vergauwen et al., 2004; Moya et al., 2010; Landlinger et al., 2012;

Baiget et al., 2014) de tenistas de competición en relación a pruebas de

resistencia o de rendimiento de golpeo, existe poca información sobre la

relación entre estos parámetros determinantes del rendimiento.

La

relación significativa encontrada entre el PDET y el UV2 (r=0,365; p<0.05) y entre el PDET y el

periodo en que se observa el UV2 (r=0.408; p<0.05), a pesar de no ser muy estrecha, indica que los jugadores

muestran una clara tendencia a disminuir la ET a partir del UV2.

Esta relación podría suponer que los sujetos que alcanzan este umbral en una

carga más elevada experimentarán el PDET más tarde. En esta misma línea, se han

descrito relaciones entre el PDET y el punto de deflexión de frecuencia

cardíaca (PDFC) en jugadores de competición (Baiget et al., 2008). La evolución

de la ET expuesta de un sujeto (figura 1), está en la misma línea que los

resultados encontrados por Baiget et al. (2014), los cuales identifican 3 fases

diferenciadas. Se observa una primera fase de adaptación (del 1er al

3er periodo) en la que, aunque la intensidad es reducida, el nivel

de ET es menor. Posteriormente se observa una fase de intensidad moderada en la

que se observa la máxima eficacia (4º y 5º periodos) para finalmente, a partir

del UV2, se produce una disminución progresiva de la ET (6º y 7º

periodos).

A

partir de una intensidad superior al UV2 el jugador entraría en un

estado de acidosis metabólica como consecuencia del aumento de la concentración

de lactato. Este hecho ocasionaría la disminución del pH, factor que está

asociado a la inhibición de la enzima fosfofrutoquinasa (PFK) y a una reducción

en la glucólisis pudiendo contribuir con el proceso de fatiga precoz (Shephard

y Astrand, 1996; Gómez, Cossio, Brousett y Hochmuller, 2010). Esta situación

metabólica esta relacionada con un descenso de la fuerza muscular (Sahlin,

1992) y afectaría negativamente al rendimiento técnico del jugador provocando

un descenso de la ET, posiblemente debido a una interacción de diferentes

factores como la disminución de la sincronización de los golpes, afectación de

la coordinación dinámica general o una inadecuada posición de golpeo. La

acumulación de ácido láctico en el músculo ejerce una influencia negativa en el

rendimiento de golpeo en tenis. Concentraciones de lactato superiores a 7-8

mmol·L-1 se asocian a una disminución del rendimiento, tanto técnico

como táctico en tenis (Lees, 2003; Davey, Thorpe y Williams, 2002). En esta

misma línea, Davey et al. (2002) observan una elevada disminución de la

exactitud de los golpes (69%) entre el comienzo de una prueba intermitente

específica (Loughborough Intermittent Tennis Test) y la exactitud observada al

final de la prueba (35,4 ± 4,6 minutos) y lo atribuyen a la elevada

concentración de lactato sanguíneo (9,6 ± 0,9 mmol·L-1).

Por

otro lado, atendiendo a que el tenis es un deporte con marcadas características

aeróbicas y anaeróbicas alàcticas (König, Huonker, Schmid, Halle, Berg y Keul, 2001; Smekal et

al., 2001; Elliott, Dawson

y Pyke, 1985; Chandler, 1995; Renström, 2002) y que durante la actividad

competitiva raramente se participa a intensidades superiores al UV2

o cercanas al VO2max (Ferrauti et al., 2001; Christmas, Richmond, Cable, Arthur y

Hartmann, 1998; Smekal et al., 2003; Fernández et al., 2005), cabe suponer que el

jugador de tenis no está preparado específicamente para realizar los golpeos en

estado de acidosis metabólica.

Considerando

el probable efecto negativo de la acumulación de lactato en el rendimiento de

golpeo, es lógico pensar que tener un UV2 más elevado hará retrasar

la aparición de fatiga en una prueba progresiva y la consecuente disminución de

la ET. Como futura línea de investigación, sería interesante observar cómo

afecta el nivel de UV2 en determinadas situaciones de juego, como

por ejemplo durante la disputa de puntos, de elevada intensidad y duración.

La

calidad de los patrones de movimiento y la coordinación de acciones específicas

en el tenis depende del esfuerzo fisiológico producido durante el ejercicio

intermitente a corto plazo (Kovacs, 2006). La relación observada entre la ET y el

VO2max (r=0.459; p<0.01) indica que los jugadores con un mejor perfil aeróbico

tienden a obtener una mejor ET, y por lo tanto, cometen un menor número de

errores durante la prueba. Aunque la relación entre estas variables no es muy

estrecha, seguramente debido a que el tenis es un deporte multifactorial y

existen diferentes factores que pueden afectar a la ET, parece que el nivel de

resistencia puede afectar a componentes de carácter técnico, posiblemente

debido a los efectos negativos de la fatiga sobre el rendimiento técnico del

jugador. La fatiga se va instaurando de forma progresiva desde

prácticamente el inicio de un esfuerzo (López Calbet y Dorado García, 2006).

Posiblemente, los jugadores con un VO2max superior, ante una misma

carga o periodo, soportan una intensidad fisiológica relativa inferior, y por

lo tanto, participan con menores niveles de fatiga. La fatiga afecta el

rendimiento de las habilidades de raqueta y se manifiesta con un pobre juego de

posición y con una disminución de la precisión de los golpes (Lees, 2003;

Fernández, 2007). Se han observado disminuciones significativas de velocidad de

servicio (3.2%) y precisión del golpe de derecha (21.1%) después de un

ejercicio que inducía fatiga en jugadores de competición (Rota y Hautier,

2012). Es lógico pensar que un VO2max superior puede colaborar a

obtener mejores resultados de ET en una prueba de resistencia progresiva. Se

ha constatado que la fatiga inducida por un entrenamiento específico de

tenis de 2 horas de juego se traduce en un aumento significativo del porcentaje

de errores y en una disminución también significativa de la velocidad de golpeo

(Vergauwen et al., 1998).

Aunque el rendimiento en tenis es de carácter

multifactorial, parece que son necesarios unos adecuados niveles de resistencia

para hacer frente a las demandas competitivas. Una buena

capacidad aeróbica permite una adecuada recuperación entre puntos y mantener la

intensidad de juego a lo largo de la duración total del partido (Konig et al.,

2001; Smekal et al., 2001). En esta línea, se ha

sugerido que para un adecuado rendimiento competitivo los jugadores de tenis de

competición deben tener un VO2max superior a 50 ml·kg·min-1,

no obstante, niveles extremadamente altos (por ejemplo, > 65 ml·kg·min-1)

no aseguran una mejora en el rendimiento en este deporte (Kovacs, 2007). Se

han encontrado relaciones entre el rendimiento competitivo y parámetros

fisiológicos máximos como el VO2max (Banzer et al., 2008; Baiget et

al., 2014) o fisiológicos submáximos como el UV2 (Baiget et al.,

2014) o el PDFC (Baiget et al., 2008).

CONCLUSIONES

Los jugadores con mejor perfil aeróbico tienden a obtener mejores

resultados de ET en una prueba de resistencia específica que evalúa

paralelamente parámetros técnicos y fisiológicos, posiblemente debido a que

participan con niveles inferiores de fatiga durante la mayor parte de la prueba.

Existe una tendencia a disminuir la ET a partir de la aparición del UV2,

probablemente como consecuencia del impacto que ejerce la acumulación de ácido láctico

sobre el rendimiento técnico de los

golpes.

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

Baiget, E.,

Fernández, J., Iglesias, X., Vallejo, L. y Rodríguez, F.A. (2014). On-court

endurance and performance testing in competitive male tennis players. J Strength Cond Res, 28(1), 256-264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182955dad

Baiget, E.,

Iglesias, X. y Rodríguez, F.A. (2008). Prueba de campo específica de valoración

de la resistencia en tenis: respuesta cardiaca y efectividad técnica en

jugadores de competición. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 3(93),

19-28.

Baiget, E., Iglesias, X., Vallejo, L. y Rodríguez, F.A.

(2011). Efectividad técnica y

frecuencia de golpeo en el tenis femenino de élite. estudio de caso. Motricidad.

European Journal of Human Movement, 27, 1-21.

Banzer, W., Thiel, C., Rosenhagen, A. y Vogt, L.

(2008). Tennis ranking related to exercise capacity. Br J Sports Med, 42, 152-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2007.036798

Beaver,

W.L., Wasserman, K. y Whipp, B.J. (1986). A new method for detecting anaerobic

threshold by gas exchange. Journal of

applied physiology 60, 2020-2027.

Bergeron,

M. F, Maresh, C. M, Kraemer, W. J, Abraham, A., Conroy, B. y Gabaree, C.

(1991). Tennis: a physiological profile during match play. Int J Sports Med, 12, 474-479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1024716

Birrer, R. B., Levine, R., Gallippi, L. y Tischler, H.

(1986). The correlation of performance variables in preadolescent tennis

players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness, 26(2), 137-9.

Chandler,

T. J. (1995). Exercise training for tennis. Clin

Sports Med, 14(1), 33-46.

Christmass,

M. A., Richmond, S. E., Cable, N. T., Arthur, P.G. y Hartmann P.E. (1998).

Exercise intensity and metabolic response in singles tennis. J Sports Sci, 16(8), 739-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/026404198366371

Davey,

P. R., Thorpe, R. D. y Williams, C. (2002). Fatigue decreases skilled tennis

performance. J Sports Sci, 20(4),

311-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/026404102753576080

Elliot,

B., Dawson, B. y Pyke, F. (1985). The energetics of singles tennis. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 11,

11-20.

Fernández, J. La fatiga y el rendimiento en el

tenis. (2007). Revista de Entrenamiento

Deportivo, 21(2), 27-33.

Fernández,

J., Fernández, B., Méndez, A. y Terrados N. (2005). Exercise intensity in

tennis: simulated match play versus training drills. Medicine and Science in Tennis, 10, 6-7.

Fernández, J., Méndez-Villanueva, A. y Pluim, B.M.

(2006). Intensity of tennis match play. Br J Sports Med,

40(5), 387-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.023168

Ferrauti, A., Bergeron, M. F., Pluim, B. M. y Weber, K.

(2001). Physiological responses in tennis and running with similar oxygen

uptake. European journal of applied

physiology, 85, 27-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s004210100425

Ferrauti, A., Kinner, V. y Fernandez-Fernandez, J. (2011).

The Hit & Turn Tennis Test: an acoustically controlled endurance test for

tennis players. J Sports Sci, 29,

485-494. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.539247

Girard, O., Chevalier, R., Leveque, F., Micallef, J.P. y Millet,

G.P. (2006). Specific incremental field test for aerobic fitness in tennis. British journal of sports medicine, 40,

791-796. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2006.027680

Gómez, R., Cossio, M.A., Brousett, M. Y Hochmuller. (2010).

Mecanismos implicados en la fatiga aguda. Rev Int Med Cienc Act Fís Deporte, 10

(40), 537-555.

Konig,

D., Huonker, M., Schmid, A., Halle, M., Berg, A. y Keul, J. (2001).

Cardiovascular, metabolic, and hormonal parameters in professional tennis

players. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 33(4),

654-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200104000-00022

Kovacs,

M. S. (2006). Applied physiology of tennis performance. Br J Sports Med, 40, 381–385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.023309

Kovacs, M. S. (2007). Tennis physiology: training the

competitive athlete. Sports Med, 37(3), 189-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737030-00001

Landlinger, J., Stöggl, T., Lindinger, S., Wagner, H.

y Müller, E. (2012). Differences in ball speed and accuracy of tennis

groundstrokes between elite and high-performance players. Eur J Sport Sci, 12(4), 301-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2011.566363

Lees,

A. Science and the major racket sports: a review. (2003). J Sports Sci, 21(9), 707-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0264041031000140275

López

Calbet, J.A. y Dorado Garcia, C. (2006). Fatiga,

dolor muscular tardío y sobreentrenamiento. López Chicharro, J. y Fernández

Vaquero, A. Fisiologia del ejercicio. 3ª edición. Madrid: Edtiorial Médica

Panamericana.

Moya, M., Bonete, E., y Santos-Rosa, F.J. (2010). Efectos

de un periodo de sobrecarga de entrenamiento de dos semanas sobre la precisión

en el golpeo en tenistas jóvenes. Motricidad. European Journal of

Human Movement, 24, 77-93.

Murias,

J. M., Lanatta, D., Arcuri, C. R. y Laino, F.A. (2007). Metabolic and

functional responses playing tennis on different surfaces. J Strength Cond Res, 21, 112-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1519/00124278-200702000-00021

Renström,

P. (2002). Handbook of Sports Medicine

and Science. Tennis. Oxford:

Blackwell Science. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470698778

Rota,

S. Y Hautier, C. (2012). Influence of fatigue on the muscular activity and

performance of the upper limb. ITF

Coaching & sport science review, 58, 5-7.

Sahlin,

K. (1992), Metabolic factors in fatigue. Sports

Med, 13(2), 99-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199213020-00005

Shephard,

R. J. y Astrand, P.O. (1986). La

resistencia en el deporte. Barcelona: Paidotribo.

Skinner,

J. S. y McLellan, T. H. (1980). The transition from aerobic to anaerobic

metabolism. Res Q Exerc Sport, 51,

234–248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1980.10609285

Smekal, G., Pokan, R., von Duvillard, S.P., Baron, R.,

Tschan, H. y Bachl, N. (2000). Comparison of laboratory and

"on-court" endurance testing in tennis. Int J Sports Med,

21(4), 242-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2000-310

Smekal,

G., von Duvillard, S. P., Pokan, R., Tschan, H., Baron, R., Hofmann, P.,

Wonish, M. Y Bachl, N. (2003). Changes in blood lactate and respiratory gas

exchange measures in sports with discontinuous load profiles. Eur J Appl Physiol, 89, 489-495. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00421-003-0824-4

Smekal,

G., von Duvillard, S. P., Rihacek, C., Pokan, R., Hofman, P., Baron, R.,

Tschan, H. Y Bachl, N. (2001). A physiological profile of tennis match play. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 33(6), 999-1005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200106000-00020

Vergauwen, L., Madou, B. y Behets, D. (2004). Authentic

evaluation of forehand groundstrokes in young low - to intermediate-level

tennis players. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 36(12), 2099-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000147583.13209.61

Vergauwen, L., Spaepen, A. J., Lefevre, J. y Hespel,

P. (1998). Evaluation of stroke performance in tennis. Med Sci Sports Exerc,

30(8), 1281-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199808000-00016

Weber, K. (2003). Demand profile and training of running-speed in elite tennis . In Crespo, M., Reid, M., Miley, D. Applied sport science for high performance tennis (pp. 41-48). Spain: International Tennis Federation.

Total number of citations / Total references: 35 (100%)

Number of citations of the journal / Journal's own references: 1 (2.9%)

Rev.int.med.cienc.act.fís.sport

- vol. 16 - number 62 - ISSN: 1577-0354